A Conditioned Choice: BVVK Failures, Voter Relocation, and the Question of Popular Will in Uganda.

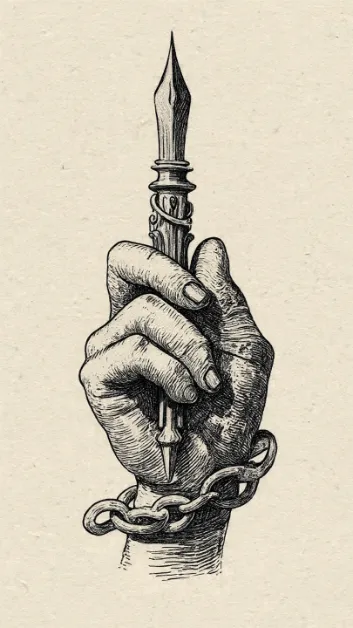

If Uganda is to protect its democratic future, electoral management must be treated as a public trust, not a technical exercise shielded from accountability.

05 Feb, 2026

Share

Save

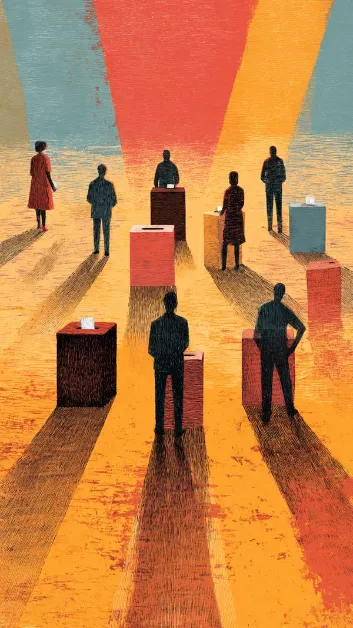

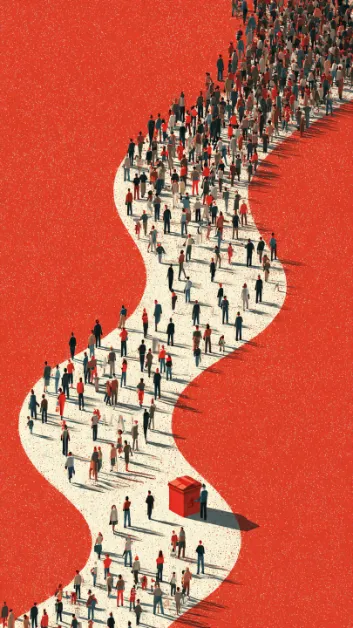

Elections derive their legitimacy not merely from turnout or declared results, but from the extent to which citizens can participate freely, knowingly, and without obstruction. In Uganda’s recent presidential elections, serious operational failures—particularly the malfunctioning of BVVK machines and the unexplained relocation of voters—raise profound questions about whether the outcome truly reflected the will of the people.

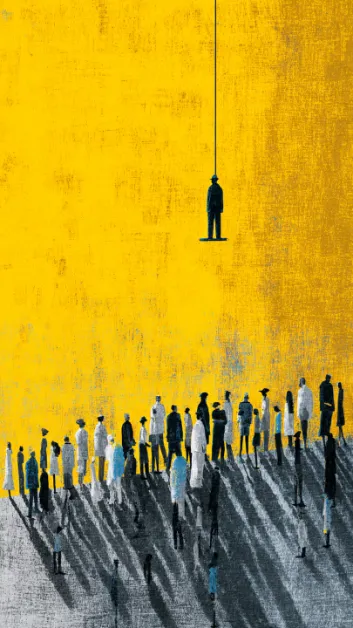

The failure of BVVK machines, especially in areas with high numbers of new voters, appeared less like a technical mishap and more like a structural exclusion. Biometric verification is meant to safeguard electoral integrity, yet when it selectively collapses at critical moments, it transforms from a protective mechanism into a gatekeeping tool. For many voters, particularly first-time participants, the breakdown of these machines meant long delays, confusion, or outright disenfranchisement. When technology fails in ways that consistently disadvantage certain categories of voters, neutrality becomes difficult to defend.

Equally troubling was the relocation of voters to different villages or polling stations without their knowledge or consent. Voting is not an abstract right; it is exercised at a specific place, at a known time, under predictable conditions. When voters arrive at polling stations only to be informed that they have been reassigned elsewhere—often far away, without prior notice—the practical effect is denial of the right to vote. Many simply give up, unable to navigate an opaque system on election day.

This practice undermines one of the most basic principles of democratic participation: certainty. A voter who does not know where they are supposed to vote is not free; they are a disoriented subject in a bureaucratic maze. Responsibility for this confusion lies squarely with the Electoral Commission, whose mandate is not only to conduct elections, but to do so in a manner that inspires public trust and guarantees equal access.

Taken together, BVVK failures and voter relocation distort the meaning of consent. The question, therefore, is not whether Ugandans voted, but whether they were allowed to vote under conditions that respected their autonomy. Did the elections portray the will of the people? In a narrow procedural sense, perhaps. But in a democratic sense, the answer is far less convincing.

What emerged was not a free and fair expression of popular will, but a conditioned will—one shaped by obstacles, uncertainty, and exclusion. A conditioned will is not the same as a stolen election, yet it is equally corrosive. It produces outcomes that may be legally defensible but morally fragile. It leaves citizens feeling that participation is symbolic rather than decisive.

Democracy does not collapse only through overt fraud. It erodes quietly through administrative choices that cumulatively narrow who can participate, how easily they can do so, and whether their participation feels meaningful. When electoral systems appear to manage voters rather than serve them, legitimacy suffers—even if ballots are counted and winners declared.

If Uganda is to protect its democratic future, electoral management must be treated as a public trust, not a technical exercise shielded from accountability. Transparent voter registers, reliable technology, clear communication, and respect for voter certainty are not optional luxuries; they are the foundations of genuine consent.

The will of the people cannot be assumed simply because an election has taken place. It must be demonstrated through conditions that allow citizens to choose freely, knowingly, and without hindrance. Until then, Uganda’s elections risk producing not the voice of the people, but the echo of a will that has been shaped, constrained, and conditioned.

About the author

My name is Abeson Alex, a student at St. Lawrence University, whose leadership journey reflects a deep commitment to service, integrity, and community transformation. I have held various leadership positions, including UNSA President of St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko, UNSA District Executive Council Speaker, UNSA Speaker for West Nile, and West Nile Representative to the UNSA National Executive Council. I also served as YCS Section Leader of St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko, YCS Federation Leader for Koboko District, and Koboko YCS Coordinator to the Diocese. In addition, I was a Peace Founder and Security Council Speaker for the peace agreement between St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko and Koboko Town College. I served as Debate Club Chairperson of St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko, District Debate Coordinator, and West Nile Debate Coordinator to the National Debate Council (NDC). All the above were in 2022-2023. My other leadership roles include Chairperson of the Writers and Readers Club, UNSA Representative in the District Youth Council, Students’ Advocate for Reproductive Health, and Students’ GBV Advocate for the District. Within the Church, I served as Chairperson of the Altarservers of Ombaci Chapel, Parish Altarservers Chairperson of Koboko Parish, and Speaker of the Altarservers Ministry in Arua Diocese. Current Positions: Currently, I serve as the Diocesan Altarservers Chairperson of Arua Catholic Diocese, Advisor of the Altarservers Ministry for both Ombaci Chapel and Koboko Parish, and Programs Coordinator of Destined Youth of Christ (DYC-UG). I am also a Finalist in the Global Unites Oratory Competition 2024, the current Debate Club Speaker and President of St. Lawrence University Koboko Students Association. Additionally, I am the Youth Chairperson of Lombe Village, Midia Parish, and Midia Sub-county in koboko district. I am one whose life has been revolving around ensuring that in our imperfections as humans, we can promote transparency, righteousness, and morality to attain perfection. I am inspired by the guiding words: Mobilization, Influence, Engagement, and Advocacy. I share my inspiration across the fields of Relationships, Career, Governance, Faith, Education, Spirituality, Anti-corruption, Environmental Conservation, Business & Self-Reliance, politics , Administration,Financial Literacy, Religion, and Human Rights. Thanks for the encounter.